Stoppies

Stoppies Part1

By: James R. Davis

There is absolutely no chance that I would teach anybody to perform a Stoppie with his motorcycle and no rational, mature, mortal human being should intentionally try to do one. But because you might be riding an unfamiliar bike, or because of incredibly poor skills, or even because of trying too hard to master emergency braking technique, you just might find yourself sitting in your saddle when the rear-end of the motorcycle lifts its rear tire off the ground.

Must you end up in that case being thrown over the handlebars and landing face first on the asphalt? Absolutely not!

Let me emphasize some concepts here. A Stoppie is NOT when your rear tire comes off the ground - that happens with some regularity, from being overly aggressive with your REAR brake (your rear shock contracts and lifts the rear tire off the ground) or when riding over bumps on the pavement. Rather, a Stoppie is the result of being overly aggressive with your FRONT brake and causing so much weight transfer to occur that the resulting weight on the rear wheel becomes negative. That is, your bike's rear-end lifts into the air and drags that rear tire off the ground with it.

Some motorcycles simply cannot, under normal conditions, perform a Stoppie. GoldWings and most Harley-Davidsons, for example. Sport bikes, on the other hand, are quite prone to doing Stoppies.

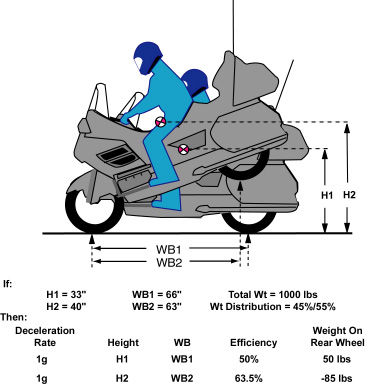

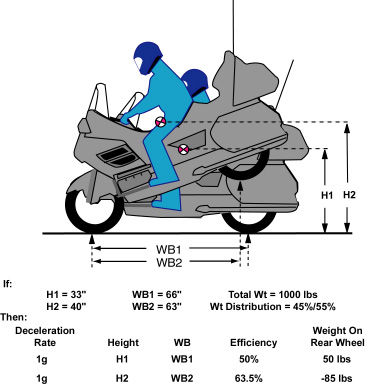

Why? The ratio of the height of the bike's CG as compared to its wheelbase determines how efficiently weight transfer will occur for any given deceleration rate. A GoldWing's Weight Transfer ratio is usually very close to 1:2 (50%) while a sport bike, because of their relatively short wheelbase, will have a Weight Transfer ratio closer to 55%.

What that ratio does is determine how much weight transfers from the rear wheel of the bike to the front during deceleration. Suppose that the combined weight of the bike and rider is 1,000 pounds and it is distributed 55% on the rear wheel and 45% on the front wheel when the bike is not in motion. If that bike decelerated at a rate of 1g (32.2 ft/sec/sec) and had a Weight Transfer ratio of 50%, then 50% of 1,000 pounds would move from the rear tire to the front tire. As there was 550 pounds on the rear tire when the bike was not moving, when 500 pounds are removed from it there is still 50 pounds of weight holding that rear tire on the ground. Now if your rate of deceleration were only .5gs, then you would have transferred only 275 pounds of weight, but if you managed to attain a 1.1g rate you would transfer 605 pounds and the rear end weight would be negative. A Stoppie would occur. HOWEVER, the traction of your front tire is almost never sufficient to support a 1.1g rate of deceleration without skidding. So BEFORE a Stoppie would occur you would wash out the front-end. That's true for the GoldWing and HD, typically.

But in the case of a sport bike with a combined weight of 600 pounds, distributed 50% on the rear wheel and 50% on the front, then at rest there is 300 pounds of weight on the rear tire. If you were to brake (decelerate) at the rate of 1g on that bike, and if it had a Weight Transfer ratio of 55%, then 330 pounds (55% of 600) would be removed from the rear tire and moved to the front one which would make the weight on the rear tire a total of MINUS 30 pounds. THAT is doing a Stoppie. In fact, the weight transferred from the rear wheel to the front on a sport bike is usually sufficient to cause a Stoppie when you reach a deceleration rate of about .95g's. Because your front tire has sufficient traction to not skid at .95g's, a sport bike will do a Stoppie BEFORE it can do a front tire skid - usually.

The following graphic depicts a GoldWing at normal posture (in the background) and doing a Stoppie in the foreground. The same is true for any motorcycle - that is, what you will observe in the graphic is that the CG rises and the wheelbase shortens when the rear tire comes off the ground:

What that means is that because the height of the CG grew and the wheelbase shortened, the Weight Transfer ratio INCREASED! Indeed, the higher the rear wheel gets, the higher (more efficient) that ratio gets and, thus, the MORE WEIGHT is moved from the rear to the front wheel.

I trust that you now see where this is leading. IF YOU DO NOTHING when your Stoppie begins, YOU WILL GO OVER THE HANDLEBARS!!!! You MUST reduce your braking effort in order to stop (or reverse) the weight transfer increase.

What that means, in turn, is that the maximum rate of deceleration you can achieve with a sport bike is that rate at which a Stoppie occurs while a bike that cannot normally do a Stoppie can stop more quickly - even without skidding its front tire.

I have mentioned a number of times that GoldWings and most Harley-Davidsons cannot NORMALLY do a Stoppie and explained why. But if you happen to be 6'6" tall and weight 300 pounds, when you get on the saddle of your scoot you will have changed the Weight Transfer ratio meaningfully. You will have raised the CG! Just like sport bikes, it is the Weight Transfer ratio that determines how much weight gets transferred at any given rate of deceleration and you will have brought that ratio above normal. In other words, you had better not grab a handful of brake!!! (But if you do, immediately release it and you will not get thrown over those bars.)

![]()

Stoppies Part2

The Bike Forum UK

Basic Stoppie

Body position--specifically, keeping your body centered over the bike--is probably the most important aspect of pulling off a safe stoppie. You must first get your body dead-center over the middle of the bike with your head straight, shoulders squared and arms stiff. Having your body off-center is what's going to cause the back end to kick out once you get the back wheel up.

Once you're up to speed and your body is properly positioned, pull the clutch in and get on the brake. Make the initial brake input pretty strong, about 80 percent of full braking pressure, then back off as the bike comes up. Weight transfer is also important. At the same time you begin braking, rock your body forward to move your weight out over the front wheel. Starting from the middle of the seat, bring your shoulders up and slide up along the gas tank until you're off the seat just a little. When you move forward, make sure your body stays as straight as possible. Remember to keep your arms straight with elbows locked so your weight shift doesn't unintentionally steer the bike one way or the other.

As the back end comes up, gradually let off the brake as you approach the balance point. As long as you're on that brake hard, it'll keep coming up. You know you're near the balance point when you're barely on the brake and that back wheel is floating--not going any higher or dropping any lower. When I'm rolling a long one at the balance point, I'm just barely on the front brake--just about five percent, just dragging the pads.

For basic stoppies, you don't really have to think about steering--just keep your arms straight and you'll keep rolling straight. It's only when you start rolling them out really long that you have to worry about steering. The only difference between a 150-foot endo and, say, a 600-foot one is being able to steer it. Steering an endo is just like steering into a corner on two wheels--you have to countersteer. If the back end kicks to the right, push on the right bar and steer into it to pull the front wheel the same way the back end is going. The higher the bike is, the easier it is to steer.

For basic endos, just ride it out to a complete stop, let the back end fall, let out the clutch and ride away. You always want your body straight right up until the moment the tire touches the ground. Any time you move, you add a steering input to the front end. Don't be too worried if the bike gets a little out of line--it can get eight to 10 degrees off and you can still ride it out without highsiding. Sometimes I'll tap the rear brake just before the back end comes down. This stops the tire spinning and tightens the chain to keep it from slapping when it hits. It sounds better--a little style thing.

180 endo

To pull this off, you really need to know how to steer an endo well. I didn't learn the 180 until a while after I learned how to steer. Instead of trying to steer the bike straight, intentionally add a steering input to bring the back end of the bike around, then control that input so it doesn't come around too fast or too slow.

To launch a 180, get the bike up to the balance point with your body centered you don't want to look for the balance point when the back end is already kicking around. The higher you are, the easier it is to steer and the smoother the back end comes around. Once you're up, start the rotation by countersteering. It takes a major input on the handlebars to make the back end come around. To get it to crank--to move all that weight around--really takes some strength. You can't just snap it around. Avoid the temptation to roll your body into the rotation--to maintain control over the bike, you really want to stay above the bike, on top of it at all times.

As the back end starts to come around, the bike will usually stall because you don't have enough momentum behind it. More height is better here--at a lower height you need more speed to snap the bike around. One way to make it spin around faster is to use more brake. The 180 endo is probably the only endo where you need to increase--not decrease--brake pressure as the endo progresses. At the end of the rotation, you're probably going to have to pull the brake back to that initial 80 percent to get it to come around. You're always at a dead stop at the end of a 180.

One-Hander

Bring the bike up just like a normal endo, and once you get to the balance point let go of the bar with your left hand. It's almost that easy. The key here is to keep your right arm extra stiff to make sure the bike doesn't drift either way when you let your left hand off. When you remove your left hand, make absolutely sure your right hand is not going to move. You don't want to have your right arm half-bent when you throw your left arm off--or hello tank-slapper, you're gonna eat pavement.

Supporting your body weight with your legs is important because you can't really use your upper body to hold yourself on the bike with only one arm. To make this work, get all your weight up on the tank (get your package out of the way first!) and jam your knees into the tank cutout to hold you up so you don't have to press on the bars.

I always throw the bike in neutral before pulling a one-hander--that way the back end won't come down when I let off the clutch.

High chair

We're moving into experts-only territory here. The toughest part of a high chair is moving into position on the bike--getting up on the tank with your feet out over the front of the bike. Like any acrobatic trick, the key is to get into position as quickly as possible. I jump up from the pegs as if I'm doing an elevator, but I jump straight over into the high-chair position. I put one hand on the windscreen, right in the middle, and jump straight up and forward, kicking my legs out around the bars as I come across. Having a hand on the windscreen allows me to gauge how far forward I'm going to jump. It looks really dramatic, but in actuality I'm only moving my butt about six inches. Your other hand can be anywhere during this time--I usually throw it up like a rodeo clown.

Once you're up and over, grab the handlebars and settle in on the tank, bracing yourself against the windscreen. Basically, your upper fairing holds all your weight. A high chair takes less initial brake to bring the back end up, and the back end definitely comes up quicker. You don't have to worry about weight transfer with this maneuver--all your weight is already over the front wheel. The back wheel also doesn't ride as high--the balance point is lower with a high chair. Feet-over-the-front endos tend to be shorter in distance because it's harder to steer the back end. You can't grab the bike with your knees and move it around underneath you. In fact, you can't even tell when the bike gets out of line, really. You don't want to come to a complete stop finishing these off--you always want a little speed left so you can roll out of it without stalling the bike because you're not going to save it when you're sitting up on the tank.

No-Footer

Once you start doing rolling endos, a no-footer is probably the easiest variation to pull off. This is basically the same thing as a regular endo, but your arms support all your weight--your feet aren't on the pegs and you can't grab the gas tank with your knees. You're basically sitting on the gas tank, so your body has to be up against it right from the get-go.

Practice these by doing regular endos and bending your knees to gradually unweight your feet and legs--the best way to tell if you're ready to bring your feet off the pegs is if your upper body is right and everything else is square. Because you don't have to worry about the handlebars moving when you bring your feet off the pegs, a no-footer is much easier than a one-hander, and you can bring your feet off a lot sooner than your hand. Just remember not to kick your feet off before you're up against the gas tank or you'll slam your junk against it and wreck yourself.

Stoppie SetUp

Confession time: I've never, ever adjusted the fork on my 2000 GSX-R750. I'm not a big guy, and the factory settings work fine for me. Just make sure you have enough preload and compression damping so you aren't at the end of the travel when you're up on the endo--if you bottom out the fork when you're up on the front wheel, you're going over. Run around 25 psi in the front tire to give a little more surface area and help it hook up better. Steel-braided brake lines are a must, and I get the best feel from Ferodo brake pads, street compound. Check the brake-mounting hardware all the time--especially if you're getting good and coming in really fast, or doing a lot of stoppies. I've had the caliper fixing bolts and the bolt that holds the caliper together loosen up everything. I like to turn my handlebars out a bit--a wider stance gives more leverage and makes the stoppie a bit easier to steer. And always always run a steering damper, turned way up. A tank-slapper when you're up on one wheel is bad news.

Getting Started

Most people think the best way to learn how to do endos is baby stoppies--you know, roll in at five mph, jam on the front brake and try not to get thrown off when the back end shoots skyward. These are so dangerous--you grab all the brake at once, causing the fork to dive too fast and the rear end to rebound and kick up, and it's easy to lose the front end or flip over when you hit the bottom of the suspension travel.

A better way is to come into your practice area fast and then slowly, smoothly grab more brake. When you feel the brake pads starting to bite, throw your weight up a little and grab just a bit more brake. If you do this methodically, you'll soon float the back wheel a few feet and everything will be smooth--none of the sharp, abrupt braking or suspension loading that will cause the front wheel to wash out or the suspension to bottom. When it feels like you're getting up too high, let off the brake slowly and you'll be back on the ground. When you're new at it, anything more than two feet will make you say, "Oh my god, I'm going to flip over." But that's the best way to learn, and if you take it slow and increase your brake pressure incrementally as your comfort level increases, you'll be floating at the balance point in no time.

Saving It

There are theories on correcting stoppies gone bad, but when you're really at the balance point and you feel like you're going over, there's not much you can do to save it. It's not like a wheelie, where you can just tap the back brake or chop the throttle and bring it back down. With most stoppies, you've got the bike in gear and the clutch pulled in. In theory, you should be able to just dump the clutch and hit the gas, and the gyroscopic force of the rear wheel spinning will actually pull the bike back down. But when you're way up and it's going over, the balance point for a stoppie is so fine and there's so much momentum carrying the bike forward that by the time you realize you've crossed over, it's too late--you're going off the bike. Well, as they say, if it were easy, everybody would be doing it.

With all that said, if anyone has a photo or a story about someone pulling off a stoppie with a ZZR250 please let me know. It can be done in theory but I've never heard of someone actually doing it. So if you know email me. paws11@hotmail.com